On Learning Math

Three principles for customizing instruction

How often have you heard people say some variation of the following?

I don’t do math.

I am terrible at math.

Please don’t ask me to do math.

I hate math.

While I did not personally harbor such strong feelings towards Math, I definitely ran into some problems (no pun intended) during my K-12 years. There were times when I considered myself “math dumb” and felt embarrased for not knowing something or understanding concepts.

Those feelings of incompetence, I would later realize, came about because of instructional mismatch, not my ability to comprehend. It wasn’t that I could not learn the information, it was that I needed a different approach.

Fractured by Fractions

One time was in the fourth grade. It was the year I got really sick. By November, I was homebound. My mom would pick up my assignments from school and I happily did them in the comfort of home when I felt well enough. Then, the school sent a tutor to my house. It was not that I necessarily needed one, but given how long I had been out of school, protocol suggested one be sent my way. The tutor, an older woman who may have been a retired school teacher, sat beside me at our tiny kitchen table and worked through the various subjects and assignments.

I’ll never forget the day I decided fractions were impossible to understand.

Keep in mind, up to this point school had been easy for me. However, when my tutor turned to the fraction section of my math book and assigned me a few equations, I had a nine-year-old meltdown. For some reason, I could not grasp the concept of adding, subtracting, and reducing fractions without the same denominator. The tension in my body escalated as she rewrote the problems and said the same things to help me get it.

I wasn’t getting it.

She sympathized with my frustration, but her instruction never changed. She didn’t use manipulatives to help me see the fractions. She didn’t hit the pause button to check in on my foundational understanding. We didn’t talk about how fractions show up in the real world. Instead, we stayed seated at that kitchen table, doing the same things, as I spiraled into tears and eventually shut down.

That was an uncomfortable moment for me as a student and a scary moment for me as a child. I wasn’t one to give up. I was not used to hitting a wall like that. It was not typical for me to need extra support in the classroom setting because I could be quite an independent learner. Until I wasn’t.

Geometrically Opposed

The second time was in 9th grade. (This is back when 9th grade was still part of middle school). I had Geometry first period. Coming from Algebra the year before, which I aced, Geometry was a foreign language to me. I actually got an “F” one quarter. My report card read, “F A A A A A”. While I laughingly read it as “Faaaaa” back then, I knowingly read it as “instructional mismatch” now.

I eventually squeezed out a C in Geometry overall, but it sure took a lot out of me, unneccesarily, I might add.

Some Questions to Ask

I recall these particular experiences because it highlights the issue many children face during their schooling years. The way an adult presents information (or is instructed to present information) may not work for every child they are attempting to reach. And if the goal of school is to inform and equip each child with foundational skills on which to build upon, then should we not make sure every child is receiving instruction that matches how he/she learns?

Instead of changing up the way math is taught and presented to some kids, we have settled on an explanation about people and math that says: “You’re either an Algebra person or a Geometry one.” Clearly, I was an “Algebra person” based on my performace in Geometry, but it really begs a few questions, like:

Why don’t teachers look at students’ past performance?

Would it not have been helpful for my Geometry teacher to know that in the same quarter I received an “F” in his class I got A’s everywhere else?

Wouldn’t this information be a red flag to him or signal that it wasn’t so much incompetence or laziness on my part, but instructional mismatch?

Would it not be better to bend our instruction to match the children versus expecting them to bend to meet the teacher’s system?

As a former teacher, I know why we don’t do the above. It’s impossible to keep track of and impossible for one person to teach to the unique needs of the 20-30 plus kids in a class.

However, if you have chosen to homeschool or your child is able to be in smaller group settings for academic work, you can customize and you should.

Here are some learning principles to keep in mind.

A Few Learning Principles

First

When it comes to learning, several conditions need to be met for children to receive instruction. Here are some I have observed over the years.

There needs to be buy-in.

The child either wants the information and/or believes the information is important and pertinent to their lives in some way. Even if that means getting through an assignment so they can go outside. Not ideal, but applies, especially in more rigid, school-like settings. Also, buy-in is personal and unique to each learner. What works for one kid may seem like crazy-talk to another. The instructor does not get to dictate buy-in. That comes from the learner.

The child accepts that the teacher or instructor is worthy of learning from.

The teacher doesn’t have to be an adult. Children learn from people of all ages, even younger siblings if they have particular skills or information they seek.

The child and teacher/instructor have a relationship in which the child feels seen and heard.

Children, like adults, may avoid overbearing “teachers” or individuals who force their knowledge onto them. No one likes being lectured to or talked at.

A successful learner-teacher relationship is built on dialogue and understanding. If you run into some resistance, keep this in mind. Your child could be feeling bulldozed by what you think is well-meaning and valueable information. Sure, you have experience on your side and you may be trying to help them avoid mistakes, but unsolicited advice or constant input about how they are or are not doing something can create distance and impact your connection. Take note. Back off. Maybe even befriend mistakes, yourself? When your children are learning something new, mistakes have a tendency to be more impactful and helpful than you simply telling them how you would do it. Furthermore, the brain actually lights up differently when we make mistakes. So, it’s possible you could be stiffling their growth by jumping in with an answer. Obviously, if they ask or seek your input, by all means, share!

Second

Effective teachers modify instruction and their presentations to match the learner.

This requires observation, discussion, and sometimes good, old-fashion trial and error. Naturally, this can take a lot of time and patience. Unfortunately, many teachers don’t have the time (or patience) to do this with a classroom full of children. There are schedules and bells to follow.

I have also seen homeschooling parents, myself included, fall into the trap of thinking that all we need to do is grab a math book off the store shelf or order one off Amazon and follow the instructions.

This is a miscalculation.

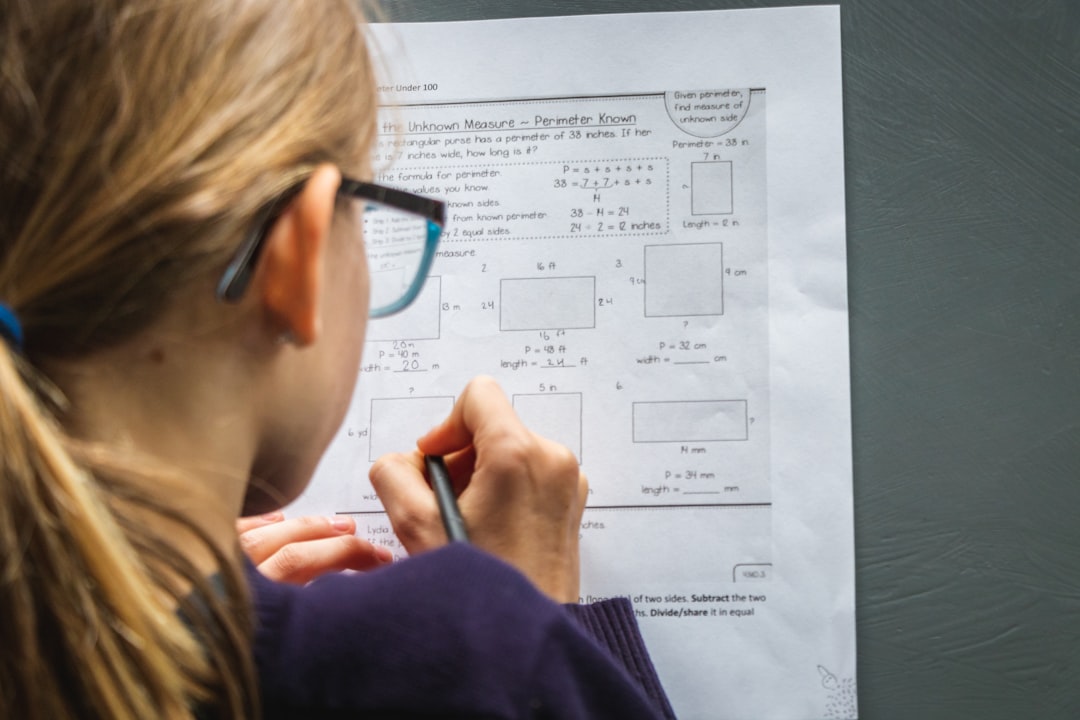

For one thing, not all math instructionals are created equally. Some are heavily language based and some are more image based. Choosing one type of curriculum may not work for all children. Remember my experience with fractions and geometry?

Instead of picking one resource, play around and find what works for each child. Some kids love manipulatives and being able to see things 3-dimensionally. Some are fine with worksheets and actually enjoy moving page by page through a math workbook. Some kids like to take their time and talk about what they are doing, while others appreciate the thrill and challenge of being timed. The beauty of homeschooling is that you get to slow down (or speed up) in order to match the needs and pace of your children.

Third

Learning is about the learner, not the teacher.

As a mentor, instructor, or guide, it’s important to stay aware of the goals and needs of the learner. If you are simply trying to “get through the curriculum” then is the learner really involved? If you are forcing or coercing learning because you believe it will somehow reflect negatively on you if you don’t, then is the Math to satisfy your ego or for your child’s actual goals and needs?

I understand that worry can come along with homeschooling. I understand what it feels like to be fearful and to wonder if you will somehow miss out on a window of skill development and to worry that your child will forever be “behind” and it’s your fault for not doing more to push the issue. However, that is a trap of school-based thinking.

The truth is, when children need/want skills to get to another level or because it is foundational to more learning, they usuallly seek it out. Also, there are natural ranges in skill development and they do no necessarily neatly align with an age or grade. This goes back to observation and communication. If you find your child needs some information to move forward, by all means, assist and provide just as you would in any other loving relationship you cherish.

Differences Don’t Mean Disabled

Watch two children interact with the same object, activity, or idea and you may notice differences in their approach and/or response. Watch a group of children and you are bound to. Why? Neurodiversity.

In 1998, Judy Singer coined the term “neurodiversity” in a thesis paper. While she used it to account for the variation in brains and thinking in ALL humans, inspired by her own experience and observations of Asperger’s Syndrome, it has morphed into a catchall term for anyone with a neurodevelopmental diagnosis. The pros and cons of this morphing is a post for another time, but suffice it to say, Singer’s original intent makes sense to me which basically says that no two brains are alike and we need to be open to the fact that there is diversity in our neurology, i.e. brain differences.

Our school centered society is largely built on one way of teaching (lecture) with an expectation that all children will learn fine from this method. Comparison is also huge in school (and homes) and it is something that can lead us to think that different means disabled. In Naomi Fisher’s newest book, “A Different Way to Learn: Neurodiversity and Self-Directed Education” she says this about comparison of children:

Those whose reactions to the education system are very different from the norm are identified as having ‘special educational needs’ or perhaps being ‘gifted’, depending on which way their differences fall. (pg 20)

She goes on to say:

When we compare all the children within a school year group, some of the differences will be down to maturity. This is something which adults typically underestimate or ignore, but the evidence of it is all around us. (pg. 21)

Bringing Learning Home

I want to reitterate Fisher’s comment that “differences will be down to maturity”, and also add that how children learn new concepts may have everything to do with the way information is presented. So, it’s important to keep presentation as well as development in mind when working with your childern on new skills.

Respect the fact that your child’s brain is different than yours. Recognize that your child is going through an active process of maturation which requires your patience and grace. Be flexible in how you offer resources, ideas, and activities. Listen to their feedback and observe how they naturally gravitate towards things, people, and experiences.

Do not get too attached to one curriculum over another. Realize you may spend money on things that don’t ever get used or get used for a season and then become irrelevant. Try not to allow this to discourage you. You didn’t “waste” money, you funded research into what works (or doesn’t) for your own child!

Also, remember that if/when your children turn down your offers, suggestions, or ideas they aren’t turning YOU down. Separate yourself from your offers.

Last, but not least, learning any subject or topic is a personal and unique experience. It isn’t something we can map out from beginning to end for anyone, including ourselves and especially our children. Instead, embrace the journey and the unfolding. Join in. Learn together. Have fun. And release yourself and your kids from the pressure to do things by school (or curriculum) imposed timelines.

When there is meaning, purpose, and internal motivation, learning can’t be stopped.

~Missy

Hello! If you are new here, welcome! You can read more of my (shorter) musings over on Instagram @letemgobarefoot. If you are new to homeschooling, are unschooling curious, or have been homeschooling for a little while but seek to transition more to an unschooling/self-directed educational mindset, Ann Hansen of Inner Parent Coaching and I teamed up to create this beautiful, downloadable e-book with you in mind. It can also be helpful if you need support explaining unschooling and self-directed education to a family member, spouse, or friend. Grab a copy here or share with a friend who could use some assurance and a confidence boost. Thank you for your support!